Contemporary Views of Comics and Literacy Education (1970s-2000s)

After the national furor over the perceived link between comics and juvenile delinquency in the 1950s and the self-censorship of the American comics industry that followed, little attention was paid to links between comics and literacy education until the 1970s. However, 1970s research into comics and reading relied heavily on opinion and anecdotal evidence, lacking much of the methodological rigor of the academic research done on comics reading during the 1940s and 1950s (Yang, 2003). For example, Haugaard (1973) focuses primarily on how her son was a reluctant reader until he began reading comics and became a reader with a motivation she describes as "absolutely phenomenal and a little bit frightening" (85). Like many educators and researchers in the 1950s, Haugaard continues the trend of approaching comics reading with cautious optimism and the perpetual reassurance that readers like her son soon outgrew the comics and moved on to more serious reading, such as "...Jules

Verne and Ray Bradbury, books on electronics and science encyclopedias" (85).

Verne and Ray Bradbury, books on electronics and science encyclopedias" (85).

Changing Views, Evolving Pedagogies

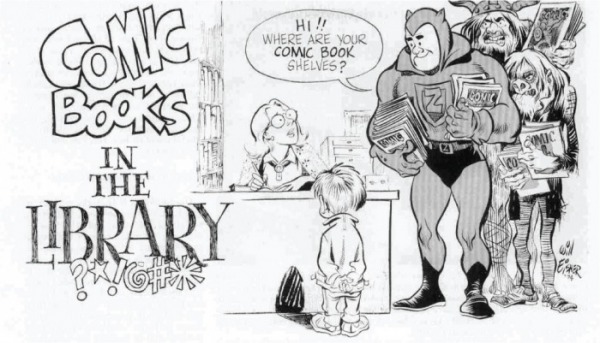

With the growth of the graphic novel movement in American comics in the last decade of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st, literacy educators, including teachers and librarians in primary, secondary, and higher education have approached the role of comics in the classroom with increasing interest and sophistication. A milestone in this cultural sea change is undoubtedly Art Spiegelman's graphic Holocaust survivor memoir Maus I: My Father Bleeds History receiving the Pulitzer Prize in 1992 (see, e.g., McCloud, 2000; Yang, 2003). The prestigious award called attention to the sophistication, literary complexity, and socio-historical significance that the medium was capable of communicating.

Krashen (2004) describes comics as a useful form of leisure reading that engages reluctant readers, or readers learning English as a second language. According to Gorman (2003): "The visual messages in a graphic novel alongside minimal print can help a reader process the story, providing a literary experience that is not fraught with the frustration that often plagues beginning readers as they struggle to comprehend the meaning in a traditional text-only book" (11).

Building on the formal affordances of comics for literacy education, and echoing earlier findings among comics researchers, Mori (2007) notes that the popularity of comics, graphic novels, and especially manga (Japanese comics) among teen readers present educators with opportunities to harness their students interests in teaching literacy practices. In so doing literacy educators "increase and diversify the voices that our students experience in the classroom and suggest to them that literature may take various forms, even comic books. Such an act is important, for through it we not only expand their reading horizons, but we give ourselves a starting point to discuss the complicated process of literary selection" (Verasci, 2001, p. 66).

In the anthology Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels: Page by Page, Panel by Panel (2007), editor James Bucky Carter and the many practicing secondary education teachers who contribute essays take up the challenge offered by Verasci, offering multiple ways of using comics as scaffolding for students to learn critical literacy skills which can also be related to subjects as diverse as classic literature (e.g. Beowulf, Dante's Inferno, The Scarlett Letter), history, and critical internet education.

Using comics creation is also seen as a means of teaching students in primary and secondary education critical literacy skills. For example, Bitz (2004) relates how The Comic Book Project after school program helped students in urban high schools make literacy connections with their life experiences by having the students write and draw comics. "The conjunction of building literacy

skills, being artistically creative, and expressing oneself in a healthy manner is a powerful combination realized through

the comic book format specifically and the process of making art in general. The children in the project asserted their thoughts and beliefs, particularly their fears and perceptions about life and occasionally dismal predictions for their own futures" (Bitz, 2004, p. 39).

Much has changed from the cautious approval and unbridled fears of the use of comics in education prevalent during the discourse over comics and literacy during the 1940s and 1950s. However, according to Jacobs (2007), approaches that use comics as scaffolding for teaching other forms of literacy don't go far enough, tending to view comics reading as a “debased or simplified word-based literacy” and ignoring the “complex multimodal literacy” required of and taught by reading comics (21).

Further information on the place of comics in multimodal literacy education, and the implications of the connections between comics and multimodality for new media literacy, can be found in the New Media section of this website.

Krashen (2004) describes comics as a useful form of leisure reading that engages reluctant readers, or readers learning English as a second language. According to Gorman (2003): "The visual messages in a graphic novel alongside minimal print can help a reader process the story, providing a literary experience that is not fraught with the frustration that often plagues beginning readers as they struggle to comprehend the meaning in a traditional text-only book" (11).

Building on the formal affordances of comics for literacy education, and echoing earlier findings among comics researchers, Mori (2007) notes that the popularity of comics, graphic novels, and especially manga (Japanese comics) among teen readers present educators with opportunities to harness their students interests in teaching literacy practices. In so doing literacy educators "increase and diversify the voices that our students experience in the classroom and suggest to them that literature may take various forms, even comic books. Such an act is important, for through it we not only expand their reading horizons, but we give ourselves a starting point to discuss the complicated process of literary selection" (Verasci, 2001, p. 66).

In the anthology Building Literacy Connections with Graphic Novels: Page by Page, Panel by Panel (2007), editor James Bucky Carter and the many practicing secondary education teachers who contribute essays take up the challenge offered by Verasci, offering multiple ways of using comics as scaffolding for students to learn critical literacy skills which can also be related to subjects as diverse as classic literature (e.g. Beowulf, Dante's Inferno, The Scarlett Letter), history, and critical internet education.

Using comics creation is also seen as a means of teaching students in primary and secondary education critical literacy skills. For example, Bitz (2004) relates how The Comic Book Project after school program helped students in urban high schools make literacy connections with their life experiences by having the students write and draw comics. "The conjunction of building literacy

skills, being artistically creative, and expressing oneself in a healthy manner is a powerful combination realized through

the comic book format specifically and the process of making art in general. The children in the project asserted their thoughts and beliefs, particularly their fears and perceptions about life and occasionally dismal predictions for their own futures" (Bitz, 2004, p. 39).

Much has changed from the cautious approval and unbridled fears of the use of comics in education prevalent during the discourse over comics and literacy during the 1940s and 1950s. However, according to Jacobs (2007), approaches that use comics as scaffolding for teaching other forms of literacy don't go far enough, tending to view comics reading as a “debased or simplified word-based literacy” and ignoring the “complex multimodal literacy” required of and taught by reading comics (21).

Further information on the place of comics in multimodal literacy education, and the implications of the connections between comics and multimodality for new media literacy, can be found in the New Media section of this website.