Anti-comics sentiment in 1950s America

After World War II, the superhero genre of American comics was largely supplanted in sales by romance, crime, and horror comics (Daniels, 1991). Mature themes in comics drew ire from the public as a cause of juvenile delinquency, a belief popularized by New York psychiatrist Frederic Wertham (e.g. Inge, 1988; Daniels, 1991). Wertham published a number of articles linking comic books and juvenile delinquency and “…supplemented his articles with addresses before groups and organizations, radio and television appearances, and newspaper interviews all designed to stimulate action against comics” (Schultz, 1949, p. 215-216).

Wertham (1948) based his arguments on the conception of juvenile delinquency as caused by “social influences that come to bear on the individual” (p. 473). The psychiatrist was primarily critical of crime comic books, but defined “crime” so broadly as to include almost any comic book, “…whether the setting is urban, Western, science-fiction, jungle, adventure or the realm of supermen, ‘horror’ or supernatural beings” (Wertham, 1954, p. 20). For Wertham, comic books constituted a public health problem akin to racism, a comparison encouraged by what Wertham perceived as racist content within the comics where the hero is “an athletic, pure-American white man” while villains are “foreign-born, Jews, Orientals, Slavs, Italians and dark-skinned races” (“Psychiatrist Asks”, 1950, p. 50).

The popularity of Wertham’s writings can in part be attributed to their publication “…in widely read and highly respected journals such as the Saturday Review of Literature, Collier's, Reader's Digest and the magazine of the National Congress of Parents and Teachers…” (Schultz, 1949). However, in addition to their popularity, Wertham’s work drew criticisms of unscientific methodologies. For example, Thrasher (1949) describes Wertham’s work as “forensic” rather than scientific, stating that the psychiatrist never provided a statistical basis for his contention that the majority of comics exhort crime and violence. Thrasher (1949) finds Wertham’s clinical study techniques similarly wanting in methodological transparency: "Although Wertham has claimed in his various writings that he and his associates have studied thousands of children, normal and deviate, rich and poor, gifted and mediocre, he presents no statistical summary of his investigations. He makes no attempt to substantiate that his illustrative cases are in any way typical of all delinquents who read comics, or that the delinquents who do not read the comics do not commit similar types of offenses" (p.203).

In April 1954, the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held hearings on comic books, and Wertham published his treatise on the social effects of comics, Seduction of the Innocent. The synchronicity “…ensured a high visibility for both and made Wertham’s work crucial to the study of the relationship between mass culture and juvenile delinquency” (Beaty, 2005, p. 155). The Senate Subcommittee stated in its findings that while there were some indications from experts (including Wertham) that crime and horror comic books could have a deleterious effect on youth, particularly emotionally unstable youth, the lack of agreement among experts indicated a need for longitudinal scientific study (Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency, 1954).The public perception that comic books were harmful to the literacy and psychological state of children grew in force. “According to the American Book Publishers council, the most intense and organized drives yet seen to curb comic books…occurred in the first six months of 1955” (Tilley, 2007).

Wertham (1948) based his arguments on the conception of juvenile delinquency as caused by “social influences that come to bear on the individual” (p. 473). The psychiatrist was primarily critical of crime comic books, but defined “crime” so broadly as to include almost any comic book, “…whether the setting is urban, Western, science-fiction, jungle, adventure or the realm of supermen, ‘horror’ or supernatural beings” (Wertham, 1954, p. 20). For Wertham, comic books constituted a public health problem akin to racism, a comparison encouraged by what Wertham perceived as racist content within the comics where the hero is “an athletic, pure-American white man” while villains are “foreign-born, Jews, Orientals, Slavs, Italians and dark-skinned races” (“Psychiatrist Asks”, 1950, p. 50).

The popularity of Wertham’s writings can in part be attributed to their publication “…in widely read and highly respected journals such as the Saturday Review of Literature, Collier's, Reader's Digest and the magazine of the National Congress of Parents and Teachers…” (Schultz, 1949). However, in addition to their popularity, Wertham’s work drew criticisms of unscientific methodologies. For example, Thrasher (1949) describes Wertham’s work as “forensic” rather than scientific, stating that the psychiatrist never provided a statistical basis for his contention that the majority of comics exhort crime and violence. Thrasher (1949) finds Wertham’s clinical study techniques similarly wanting in methodological transparency: "Although Wertham has claimed in his various writings that he and his associates have studied thousands of children, normal and deviate, rich and poor, gifted and mediocre, he presents no statistical summary of his investigations. He makes no attempt to substantiate that his illustrative cases are in any way typical of all delinquents who read comics, or that the delinquents who do not read the comics do not commit similar types of offenses" (p.203).

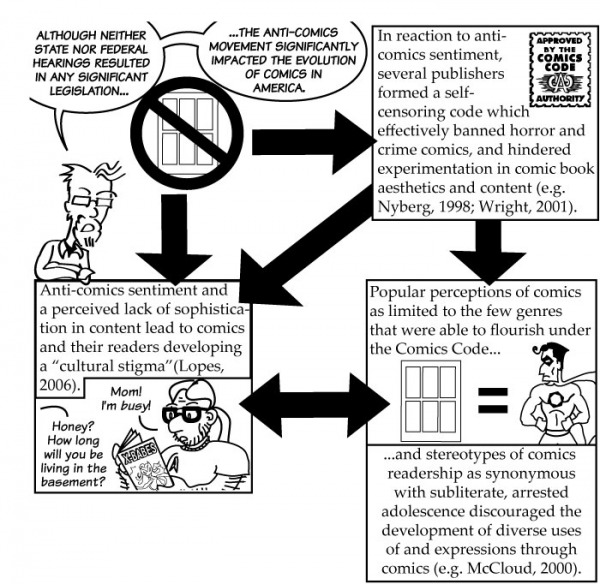

In April 1954, the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency held hearings on comic books, and Wertham published his treatise on the social effects of comics, Seduction of the Innocent. The synchronicity “…ensured a high visibility for both and made Wertham’s work crucial to the study of the relationship between mass culture and juvenile delinquency” (Beaty, 2005, p. 155). The Senate Subcommittee stated in its findings that while there were some indications from experts (including Wertham) that crime and horror comic books could have a deleterious effect on youth, particularly emotionally unstable youth, the lack of agreement among experts indicated a need for longitudinal scientific study (Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency, 1954).The public perception that comic books were harmful to the literacy and psychological state of children grew in force. “According to the American Book Publishers council, the most intense and organized drives yet seen to curb comic books…occurred in the first six months of 1955” (Tilley, 2007).